What You Are Hearing

Audio is unique in that it occupies the Electromagnetic space of electronic signals, the Mechanical space of transducers and the Tympanic space that we hear.

Audio is unique in that it occupies the Electromagnetic space of electronic signals, the Mechanical space of transducers and the Tympanic space that we hear.

Most of us have heard the often cited range of audio as 20hz to 20,000hz. But for the most part we don't really know what that means or why it matters. For most it's just an expected range of numbers when discussing speakers and amplifiers.

It is surprising to notice how many people don't know what these tones actually sound like. There is a tendency to estimate pitch either too low or way too high, largely because they've never actually heard these sounds as distinct entities or ranges.

But, if you want to set up a good quality system, you really do need to be able to judge what ranges of sound need to be tweaked when positioning speakers or setting an EQ curve in your amplifiers. Even a very general familiarity can help you achieve far better results and might save you some money on mistaken purchases.

So lets explore and learn what various parts of the audio spectrum actually sound like...

Frequency and wavelength

Sound travels in waves that alternately pressurize and rarify the air. Every wave has three basic properties; Amplitude, Frequency and Wavelength.Amplitude is the size or loudness of a sound. The more difference between pressurization and rarification, the louder the sound will be. This is usually measured as Decibels or DB.

Frequency is a measure of how often something happens in a given time period. In this case we are concerned about how many times per second a sound wave completes one full cycle of pressurizing and rarifying the air. This is commonly measured as "HZ" or "Hertz" but can also be cited as "CPS" or "Cycles Per Second".

Sound travels in air at a more or less fixed speed so as the frequency increases, the distance occupied by one full cycle of pressurization and rarification decreases. Audio wavelengths run from 17.5 metres at 20hz to 1.7 centimetres at 20,000hz.

A handy calculator for converting between audio frequencies and wavelengths is on Translator's Cafe.

Full range sound

In audio terms "Full Range" means that something can use the full 20 to 20khz range of audio frequencies. This is highly desirable in our electronics so that every sound in the audio spectrum is amplified and faithfully reproduced for us.To hear what the full 20hz to 20,000hz audio range sounds like, click the button below.

Don't worry if you don't hear sound at the beginning or end of the sweep. Most people do not hear the full 20 to 20,000 range. At conversational levels average hearing runs from about 40hz to 15,000hz but falls off rapidly outside that range. Also, many speakers (even the expensive ones) cannot reproduce the full audio range.

Audio for electronics

Our electronics need to cover the entire range of human hearing, preferably with some space to spare. It is not uncommon for modern audio equipment to cover a range from 3 or 4hz all the way to 30,000hz or more. This is to ensure best performance within the standard 20-20k range.

Our electronics need to cover the entire range of human hearing, preferably with some space to spare. It is not uncommon for modern audio equipment to cover a range from 3 or 4hz all the way to 30,000hz or more. This is to ensure best performance within the standard 20-20k range.

It is often helpful to split the audio spectrum up into Octaves. Each octave represents a doubling of frequency from the one below it. Which fits in very well with the way electronic devices behave in the real world. It is commonly used in service and measurement.

For a home system, it helps to be familiar with these tones so you can tell which octave a sound falls within when adjusting room correction, equalizers, sub-woofers, etc. A keen ear can help you isolate and solve a lot of problems.

In this case we divide the range on the beginning of each octave starting at 20hz and ending at 20,000hz:

When first hearing the octave markers as pure tones, many people will be surprised to find out how shrill the upper octaves actually are.

Audio for speakers

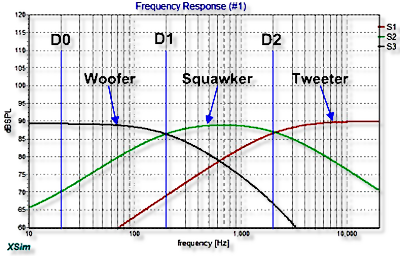

Because not every speaker can handle the full range of audio, the spectrum has also been divided into 3 "Decades". A decade is a range starting at one value and ending at 10 times that value.

Because not every speaker can handle the full range of audio, the spectrum has also been divided into 3 "Decades". A decade is a range starting at one value and ending at 10 times that value.

This method of dividing up the spectrum has proven very useful for speaker builders. Most sound drivers will not handle the full 20-20k range without breaking up or becoming uneven. So they use drivers designed for each decade and design crossover networks to steer the frequencies to the appropriate drivers.

The three audio decades are marked as D0 which is the bass range from 20hz to 199hz, D1 which is the midrange covering 200hz to 1,999hz and D2 is the treble range from 2,000hz to 20,000hz.

In a 3 way system, the large Woofer would cover D0 (bass) the Squawker would cover D1 (midrange) and the Tweeter does D2 (treble). In two way systems which typically use smaller drivers, the Mid-Woofer would cover D0 and D1 (bass and midrange) with the Tweeter working in D2 (treble).

Harmonics

In practice it is nearly impossible to produce a pure tone. There is almost always some minimal distortion present in the form of harmonics that can affect what we hear.A harmonic is an extra tone that occurs at octave multiples of the main tone. That is if we produce a tone at 440hz (for example) we are also producing tones at 880hz, 1320hz, and on each octave above that. When the harmonics become strong enough, they will become audible.

In electronics we tend to think of "Harmonic Distortion" as a bad thing since it is a sound coming out of a device that we did not feed into it. That is, it's seen as an error.

Side tones

A side tone is a secondary sound that is not harmonically related to the first. These can be any mixture of tones, in almost any number. As with the harmonics, these too can become audible if strong enough.It should be obvious that when testing things with pure tones, anything that is output other than the pure tone is considered distortion. Side Tones often take the form of hum or hiss which can be very annoying.

Music is a subset of audio

Music has been around a lot longer than modern electronics.

Music has been around a lot longer than modern electronics.

Centuries ago composers and performers worked out an agreement about which notation on music score represented which musical notes. To perform together they also had to agree what pitch (or frequency) each note represented. This gave us the Chromatic scale commonly used in western music. For example: Middle A has to sound at the same pitch (440hz) on all instruments if the music is not to sound discordant.

We also need to be aware these scales and divisions were not designed to fill the audio spectrum. They were designed to produce a pleasant listening experience long before anyone even dreamed of electronic reproduction of music. Our current ability to examine frequency and timbre of musical notes is definitely the new kid on the block.

The standard for musical tuning and range is the piano keyboard which occupies seven octaves within the audio spectrum. Musical octaves are divided on the pitch of the C note in each octave. An 88 key piano keyboard covers seven octaves with three outlier keys below the C in octave 1. Like this:

From the home audio perspective, music now exists as a subset of the overall audio spectrum. Despite the tendency to asses some instruments as very shrill or deep sounding, music actually only occupies a small segment of the overall audio spectrum. The lowest fundamental note is at 27.5hz and the highest is at a mere 4,186. Although the highest note (C8) is very shrill sounding it actually occurs less than a quarter way up the overall spectrum.

A more detailed listing of each key's frequency can be found on Wikipedia's Piano Key Frequencies page.

Musical voices

If audio was as clean and simple as the pure tones we've heard so far everything would sound the same. We would not be able to distinguish a jackhammer from a drum or a jet engine from a guitar. Music, as we know it, would not exist.

If audio was as clean and simple as the pure tones we've heard so far everything would sound the same. We would not be able to distinguish a jackhammer from a drum or a jet engine from a guitar. Music, as we know it, would not exist.

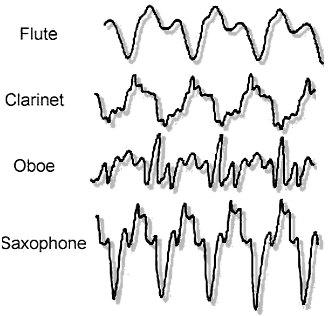

In the real world, every sound is a mixture of fundamental tones, harmonics and side tones, in various combinations and at various levels. This gives each sound it's unique character.

Music takes full advantage of this by deliberate use of both harmonics and side tones, giving each instrument its own voice. This also gives each instrument a unique waveshape that we can identify, as shown on the right. This is called Timbre.

A good example is the lowest note on a piano keyboard. Despite it's 27hz fundamental frequency being almost inaudible, it makes lots of sound. It is the harmonics and side tones, the piano's voice, you are actually hearing.

Musical Bandwidth

The fundamental frequencies of almost all instruments fall within the 27.5 to 4186hz range. While this should be obvious for horns, strings and keyboards, it also includes instruments that might surprise you. The booming loud tympani typically works around 100hz. The big shrill crash cymbal probably rides at about 500hz. Even that tinkly little triangle is likely in the 2khz range.This doesn't mean the harmonics do not get well beyond the 4,186hz top note. In fact there is considerable harmonic content in the 4,000hz to 8,000hz range. But the levels roll off as the frequency increases until around 12,000hz. Beyond this the upper octave (O9) in the overall bandwidth is pretty much silent.

To illustrate this here is a short clip of "Don't bring me down" by the Electric Light Orchestra. The first clip is the song played full range. The second is played with a low pass filter at 4200hz which is just above the highest piano note. Notice that all the instruments are still there but now it sounds dull, lifeless. The third, high pass, button lets you hear the harmonic content the low pass filter removed.None of the information above 4200hz is fundamental music but it is part of the music and it is needed to preserve the voicing and distinctness --the timbre-- of each sound. Thus, the added bandwidth in the audio spectrum of 20 to 20,000hz.

Summing up

The standard 20hz to 20khz bandwidth was reserved in the 1950s to accommodate both music and voice ranges. It basically covers the range of human hearing plus a bit. Hopefully this quick overview will help you understand how the audio spectrum works and what various points along the spectrum sound like. When you are familiar with the actual pitch of music and various sounds it is much easier to identify and fix problems in your audio setup.If you would like to experiment further, you can download all of the Sound Samples in a zip file.